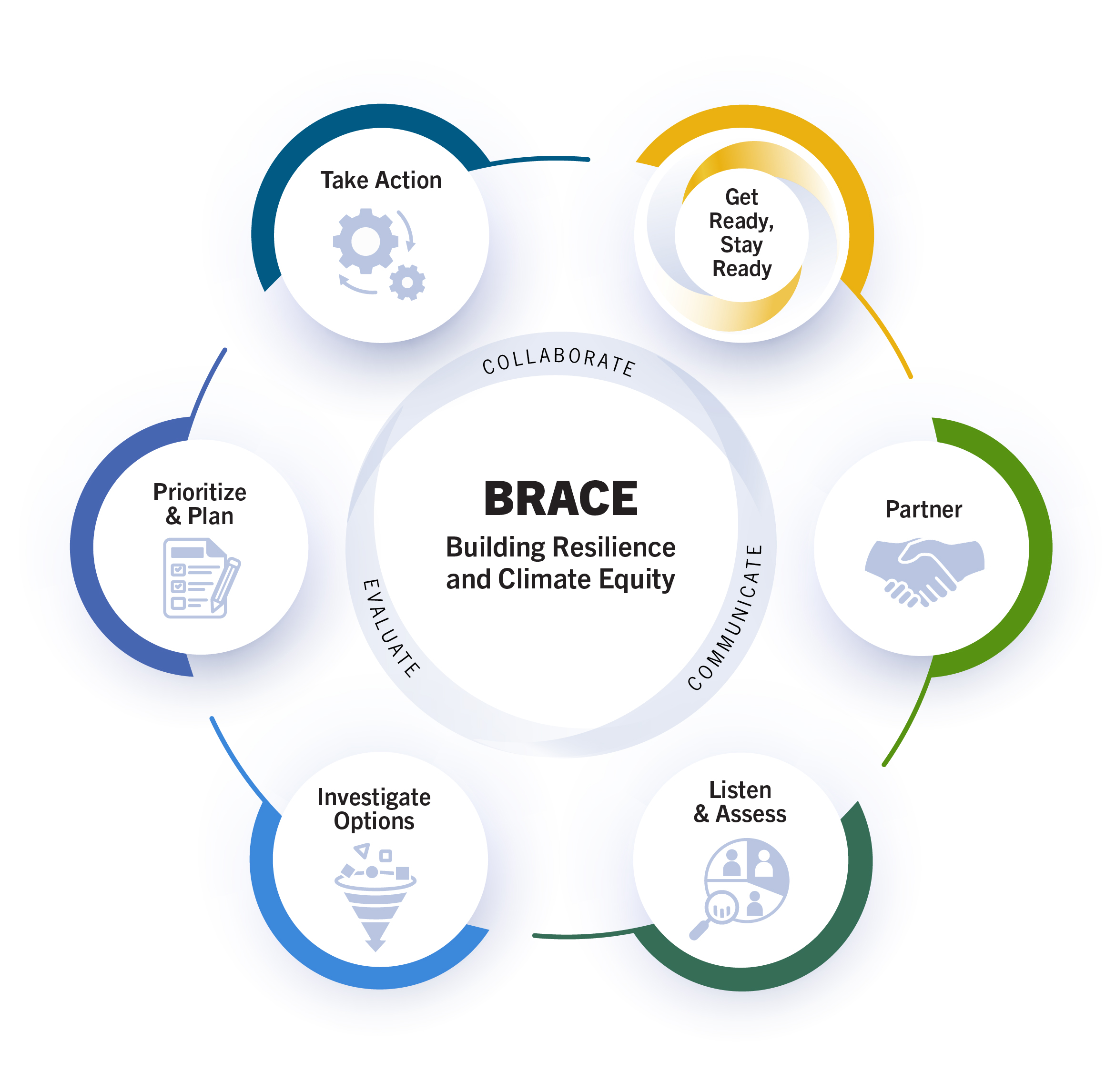

Building Resilience Against Climate Effects

What is BRACE?

BRACE helps health professionals and health departments at all jurisdictional levels partner with communities to assess climate and health threats, co-develop effective strategies, and act to promote health and climate resilience.

Justice, Equity, and Belonging

BRACE recognizes that climate action must center justice, equity, and belonging to address widening disparities in climate change harms, achieve true resilience, and create opportunities for all people to thrive. BRACE strongly encourages users to prioritize justice, equity, and belonging throughout each of the elements and associated tactics. In using this trio of terms, BRACE seeks to increase fairness, support a more equal society, and reduce the harms of systemic oppression and marginalization.

Six Elements of BRACE

Each element guides users through a process for taking public health climate action and is organized by key tactics that detail how to implement the necessary activities. See the full Guide for resources and more.

More resources

Read AJPH's article on "A Flexible Framework for Urgent Public Health Climate Action."

Funding Acknowledgement

The Building Resilience Against Climate Effects Framework was developed through a CDC Cooperative Agreement with the Prevention Research Center at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School (RFA-DP-22-003, U48DP006381). The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC/HHS or the U.S. Government.